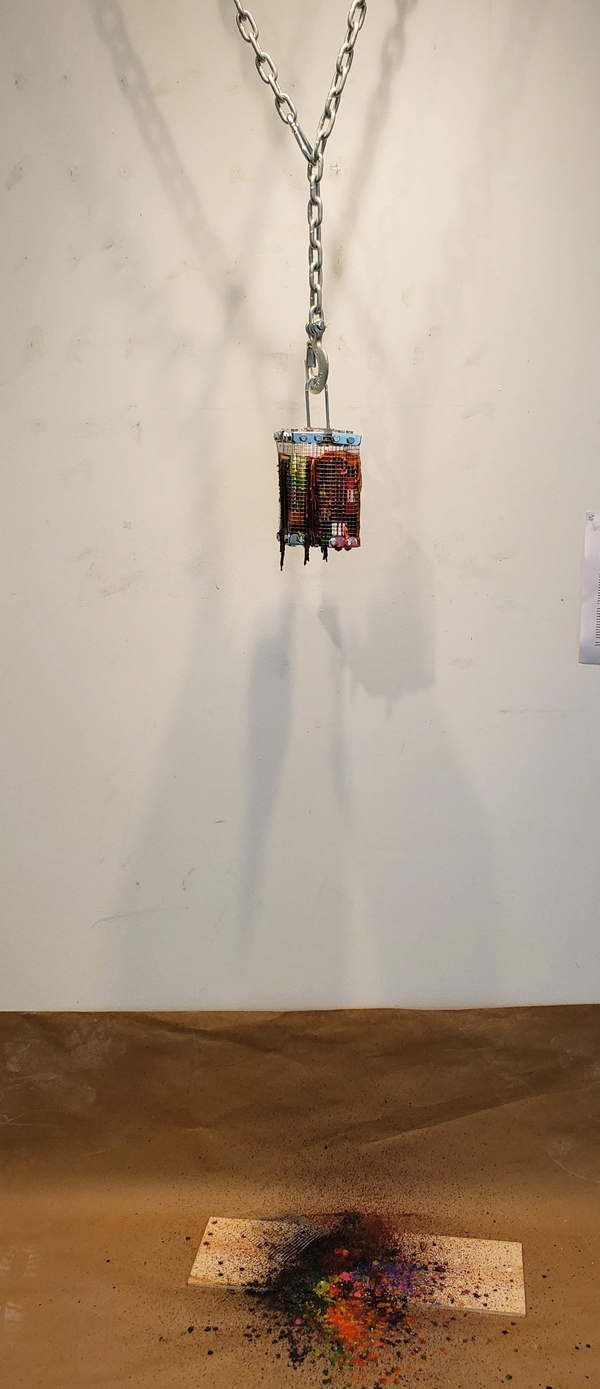

John Cage Bubblegum

2019

Crayons, galvanized and zinc-plated steel.

1.9m H, 0.12m W, 0.12m D

The cage can be viewed at any level, but it most prefers to be quite high, at about shoulder level. I encourage the viewer to actuate the mounting height with the chain and carabiner– it is quite the auditory experience. It need not be still– it can be pushed and flung, allowed to orbit through space. It is also content to simply hang- though in this case, the viewer should circulate around the piece, as to see it in the round. It is also quite nice when viewed from above, if the viewer has a ladder on hand. The underside is underwhelming. The name is a sort of tongue-in-cheek throw to my feeling that the minimalists didn’t really have any fun. Yves Klein definitely had fun. But Donald Judd, Agnes Martin, Frank Stella, I don’t think they really had any fun. I’m not sure if John Cage had fun, but it doesn’t really sound like it. If John Cage chewed bubblegum, I think he’d like this piece.

I appreciate minimalism. My favorite artist has always been Ellsworth Kelly, and I think he excludes the unnecessary more radically and profoundly than any of his contemporaries. His distillations of entire landscapes into their single most essential element are perfect. But the reductions for which Kelly is famous are not the works I find most compelling. I’ve long been taken by his color field works, such as his Color Panels for a Large Wall and his Spectrum Colors Arranged by Chance series. To more precisely articulate my attraction to these panels, I sought literature surrounding Kelly and this specific moment in his career. Upon discovering there isn’t really any, I realized my infatuation was simply with the richness and vibrancy of his hues. Kelly’s panels are the best medium for the pure expression of color. But because Kelly is perfect– the deepest possible abstraction of chromatic expression– I can’t do what Kelly did. Not because I cannot replicate his craftsmanship (though I can’t), but because any variation on his works will simply be incorrect, divergent from the medium most specifically appropriate for the manifestation of color.

I posit that minimalism must engage the absolute purest expression of its artistic concept to be empowered by its minimalism rather than compromised by it. So I put colors in a cage, and the colors wanted out. I’m glad they did; the cage is the wrong vehicle for color. The colors escape their container in a dazzling expression on the floor below, stochastically brilliant, enchanting in a way that the imperfectly minimalist apparatus from whence they came cannot be.

I further interrogate the artistic fetishization of imperfect minimalism by rendering the work as a product of industrial manufacture. The cage (the object that has literally been elevated to sculptural superiority) is hot-swappable, simply clipped to a stout metal hook. It seems as if it is a product caught in the middle of its casting, suspended from a foundry’s chain as it is rushed from one process to the next. The sculpture is modular; its principal component can be trivially exchanged for anything else, perhaps another art object, or the next product of the assembly line. Though it is often the product of industry, sculptural minimalism seldom operates in the structural language of industry. Does this omission detract from minimalism’s absolute material honesty? I’m skeptical of reduction in general, be it in science or art. Only the best reduction has any value– imperfect reduction is simply wrong. I created John Cage Bubblegum to elevate this concern to artistic legibility. John Cage Bubblegum refuses perfection.